(PhotoCairo 5 was held between 14 November and 17 December 2012. It was organized by the Contemporary Image Collective in Cairo and curated by Mia Jankowicz.)

PhotoCairo 5 was not photography and not Cairo. It was a mélange of video, conceptual art, installations, and photographic productions by local and international artists that generally required knowledge of the English language and international art practices and theories to be comprehensible. Indeed, this would have been a fine exhibition in a European or American city where the fragmentation of society has led to art made for specialists shown in institutions that attract small audiences. So, if life and death, brutality and corruption, individual agency and powerlessness, the role of religion and faith in society, the economics of marginalization and resistance, physical and emotional suffering, the labor movement, the rapid and unchecked development of the mega-city are disrupting your daily life, PC5 will nevertheless “allow [you] to witness the awakening of a radical reality” [curator’s text] unencumbered by the realities of Egypt today.

Of twenty or so works exhibited, only A Monument of Buzzwords (2012) by Samir El-Kordy investigated Egypt’s obsession with the revolution. An inscrutable architectural proposal uses diagrams, texts and photographs to show a massive, richly-tiled wall bisecting streets and absurdly carving downtown Cairo into uninhabitable cantonments in order to commemorate the sites of the Egyptian Revolution. Text and statistics guarantee the monument’s feasibility. This could very well be the generals’ answer to erecting, removing, and re-erecting a dozen walls around parliament, the Ministry of Interior and the Presidential Palace. This wall is replete with observation decks for great views and photo opportunities. El-Kordy, an architect, shows us how power constructs physical and other obstacles to our daily lives and aspirations as labyrinthine and insidious as Israel’s separation wall.

Even when titles, texts, and captions were translated for the benefit of the audience, PhotoCairo 5 remained a foreign language. Every Subtle Gesture (Basim Magdy, 2012), Illustrations of Future Narratives (Iman Issa, 2012), and even A Monument of Buzzwords make little sense in Arabic unless you read the English as well. Two exhibits by very successful Egyptian artists relied entirely on English, where Arabic was merely a footnote or digression.

.jpg)

[From Every Subtle Gesture by Basim Magdy, 2012.]

Even entirely visual works like Illustrations of Future Narratives required knowledge of a language that only an elite might obtain in this country. These five silent projections under one title test a viewer’s attention span. Did she blink? Is the bird in every image of the sequence? Is the clock pendulum getting closer and shifting color? Do I really need my head examined in this way? Muybridgesque sequences of stills are exercises in cleverness and an aesthetics devoid of content. A single unique video in this piece offers a series of stills of an abundant urban Cairo juxtaposed with images of new desert developments. At strobe-speed the pictures rush headlong from urban to suburban, from settled to vacant, from lush Nile to barren lands. Images of an outdated tank and the October War Panorama punctuate and provoke anxiety. The relentless pace taxes the eyes, and a loose narrative begins to emerge through form and content.

No other works in PC5 even winked at current debates in Egypt. It is a curious phenomenon that the elite young photographers of this country – whose work has been exhibited in the New Yorks and biennales of the photography/art world – have chosen to ignore the realities of their country. If serious cutting-edge Egyptian photography of the past decade offers no sign about what the Egyptian revolution is, how it might have developed or who revolted, then questions arise about the role of this photography in society. What is its conceptual basis and for whom is it being made?

We have profound physical and emotional needs that are not satisfied by the way we live and are governed, we have serious and vital questions about the direction our society is taking, and we have super-educated, internationally-exhibited photographers who are unwilling or unable to deal with these realities. During the revolution, control of the image of Tahrir Square was contested and won by ordinary people and activists who created and diffused an alternative photography that was incorporated almost immediately into social and political memory. How have gifted and privileged Egyptian photographers used their medium for the benefit of society? What is their relationship to society’s centers of power?

Have our elite photographers contributed to the development of the medium in Egypt or have we blindly appropriated styles and approaches that ape photographers elsewhere? If photographs are written in the language of the cultures in which they are made, what then is an emerging photographic vernacular in Egypt? Have the institutions that heralded a sea change in the exhibition and practice of serious photography such as the Townhouse Gallery of Contemporary Art and Contemporary Image Collective promoted an inclusive kind of photography that responds to important debates in Egypt or have they promoted an Egyptian photography that reinforces the art market’s consumer values?

Two simultaneous exhibitions offered a counterpoint: Hany Rashed’s cartoon-like paintings at Mashrabia Art Gallery and Liminal Spaces, a video exhibition by three international former artists-in-residence at Townhouse Gallery. Rashed’s paintings reconfigure the events and icons of the revolution in an acerbic but light-hearted syntax that also incorporates pop culture images from around the world. His painting and collage has always been personal and obsessive, local and specific, while simultaneously transcending its local roots. But Rashed’s work does not alienate local audiences because his strength lies in his local environment and experience.

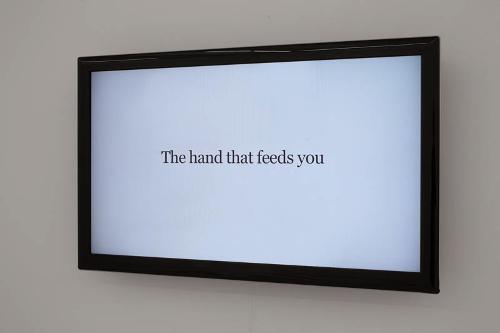

In contrast, A rose is a rose is a rose… (2012) by Jane Jin Kaisen in the Townhouse exhibit does not invite easy reading. This highly literate, English-language video poem throbs on the screen with the rhythm of a lighthouse beacon guiding ships ashore. Kaisen transforms a foreign language into an implacable commentary on the Egyptian revolution and its repercussions by reconfiguring its own language. We go from “a rose is a rose is a rose/is a site of contestation,” to “virginity tests/conducted by the military regime/a deliberate targeting of women/protestor associated with prostitute,” to “a turning point no turning point/half a revolution is better than none/half a revolution is no revolution/no revolution is not enough/a rose for every martyr is too many.” No account can do justice to the experience and impact this video generates.

[From A Rose is a Rose is a Rose… (2012) by Jane Jin Kaisen.]

Viewing Rashed and Kaisen’s works were a reminder that less than a kilometer away, almost two years before, revolution shook Egypt to the core. Their works are part of the continuing aftershock. They did not retreat to their studios to intellectually ponder the things that really matter. Their art does not leave the problems of society behind. It does not substitute spectacle for experience. Rather, their work is deeply invested in sharing another kind of engagement with and for the society in which it is exhibited.